The last several issues of the Wilderness Medicine Newsletter have been devoted to musculoskeletal and joint issues and the common injuries and treatments associated with these two topics. By contrast we wanted to present something a little different that addresses, at least, some of the underlying causes of accidents in the backcountry. To that end we spoke with Jed Williamson. Jed is well known in the climbing community for his participation in signature expeditions and as a former President of the American Alpine Club. He may be more generally recognized as the managing editor of Accidents in North American Mountaineering, an annual publication that lists accidents and offers assessments of the root causes of those accidents.

We have always thought of Jed first and foremost as an educator. As can be seen below, his credentials speak volumes about his contributions to the world of education, contributions that are sometimes overlooked in the context of his broader resume. We feel that Accidents in North American Mountaineering represents a tremendous resource of case studies, making it a valuable teaching tool. Through the following interview, we hope to make sure that everyone in the world of Emergency Medicine is aware of this resource. We are delighted to have the opportunity to talk with Jed and give him an opportunity to share some of his insights.

The Editorial Staff

Wilderness Medicine Newsletter interview with Jed Williamson:

WMN: Jed, you are known for having a list of the top reasons that mountaineering accidents happen. Would you please review for the WMN what that list is?

JW: There are a lot of them, but when it comes to making decisions with a poor outcome, at the top of the list are: a desire to please other people and trying to stick to a schedule.

I mean clearly it varies from incident to incident. In addition, you have to look at other factors: for example, the big three—unsafe conditions, unsafe acts, and errors in judgment, but the top two are making decisions just to try to please other people or insisting on sticking with a schedule, particularly if conditions clearly dictate that it would be unwise to continue on.

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid is a life-threatening illness caused by the bacterium Salmonella typhi. It is also known as gastric fever, abdominal typhus, infantile remittant fever, slow fever, nervous fever, and pythogenic fever.

Paratyphoid fever, also known as enteric fever, is a less serious illness that is also caused by Salmonella bacteria, but the symptoms are very similar to those of Typhoid Fever.

Warning: Typhoid fever is different from Typhus. Typhus is an illness caused by the bacterium Rickettsia while Typhoid is caused by Salmonella bacteria.

Pathophysiology of Typhoid:

Salmonella typhi lives only in humans – there is no other reservoir in nature besides humans.

The Salmonella typhi is spread from one person to another via the oral-fecal route where food or water has become contaminated by poor sanitation. Inadequate conditions have allowed the water source to become contaminated with human excrement – urine and feces, or by improper food handling and preparation.

Salmonella can also be spread by flying insects, such as flies, that feed on feces and then land and walk on food that you might then eat.

Flies: Their dirty little foot prints on your food is enough to spread Salmonella and other intestinal illnesses from one animal to another.

Once the Salomella bacterium has been consumed in food or water, it passes through the stomach into the intestinal tract where is multiplies and invades the mucosa wall. Within the mucosa wall the Salmonella bacteria are phagocystized (surrounded and consumed) by macrophages (white blood cells). If the bacteria manage to avoid the immune system in the gut wall, they will then invade and multiple in the blood stream.

It is the invasion and multiplication of the Salmonella in the bloodstream that causes the signs and symptoms of Typhoid.

While I was recently back in Zambia at Overland Missions teaching another Missionary Wilderness First Responder course as part of the Advanced Missions Training course that they do twice a year. I caught up with Mariel and after many hugs she told me this story and showed me the bone fragments from his finger, which she had saved for me to examine. I asked her to please write down this marvelous event, so we could share it with our readers.

Mariel is a staff member and one of the expedition leaders for Overland Missions based at Rapid 14 on the Zambezi River in the village of Nsongwe, Zambia. She is a great example of why we do what we do at SOLO. She recognized a life-threatening infection and applied the skills that she had been taught in her Missionary Wilderness First Responder course that she had taken at the Overland Missions base in Nsongwe the previous year. She saved his life and I am sure she will see him again on her return trip.

Frank Hubbell, DO

Medical Editor

Wilderness Medicine Newsletter

The Path to Peter

by Mariel Brantley

Winter in Africa will always take you by surprise. Your mind has to slightly bend to equate cold and Africa in the same realm. However, no matter how long it takes you to catch up with the paradoxical weather, it doesn’t change the fact that come morning, you will struggle to get your blood flowing again because of the cold. It was day two of our expedition. We hit the dirt path at 9am and had no plan of returning until we found what we were looking for. Equipped with a team of five and one translator, we were searching for the unreached. We pushed ourselves to go faster, further, and harder than the day before. I knew we were finally meeting our goal when we found ourselves on the far side of the hills, delicately dangled in the balance of a broken log and four slippery stones while crossing one of the river beds.

If I had any doubt in my mind if I was awake, it definitely went away as we walked into the first village. As I stood there looking at the villagers, it was as though my sense of smell overpowered my sight. I immediately knew something was wrong. After all, the scent of decaying flesh is unmistakable. Before I could get the words out, I was already making my way toward a man standing in the back. I said, “Who is hurt here? Someone is sick. You sir, what is wrong?” The man looked up at me with the look of shame and fear. I approached him and saw a dirty, tattered strip of cloth covering his finger and asked him to remove it. He slowly removed the cloth to reveal an extremely swollen and infected finger. I asked his name and what had happened. The man said his name was Peter, then explained he had been in a fight and was bitten by the man who attacked him. He said that it had happened about two months prior. My eyes darted across every detail I could absorb like one of those rapid freeze frame shots you see in a movie. I observed the wound and could clearly identify the track mark of the infection trailing all the way up his arm, past his elbow and to the middle of his bicep. Severe infection + closed wound + clear track line + raised body temperature = serious trouble. I looked up at him with a sense of urgency and said, “Sir, please, you must come with us to our camp.”

https://www.wildernessmedicinenewsletter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/wmnlogo20151.png00WMN Editorshttps://www.wildernessmedicinenewsletter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/wmnlogo20151.pngWMN Editors2012-07-09 13:32:082012-09-21 17:54:59Wilderness Treatment of Severe Infection: a First Hand Account

A couple is hiking down a trail into the Grand Canyon, enjoying the day and looking forward to reaching some shade at the bottom. The trail is in good shape with the occasional rock in the middle of the trail. The female companion unfortunately stubs her toe on a rock and falls. She falls forward, downhill, with a 40# pack on her back. She instinctively reaches out with her right hand to control the fall. As her right hand impacts the ground with her arm straight, she feels an intense searing pain in her right elbow, a sharp snap, and her arm collapses. Crumbling onto the trail, she immediately rolls over and grasps her right elbow in her left hand, letting her companion know that her right elbow is in excruciating pain.

Upon examination, he finds that the elbow is very tender to palpation and is locked in position at 90 degrees of flexion. The elbow is deformed and looks like the butt of a gun, a gunstock. He also notes a decreased sensation in her fingers and no radial pulse at her wrist. Over the next half hour her right hand goes from pale to cyanotic, with pins and needles sensation in her fingers, and she is unable to move her fingers.

ELBOW FACTS:

Elbow pain is the second most common reason to see an orthopedic surgeon, the first reason being shoulder pain.

The “funny bone” is not a bone. It is actually the ulnar nerve. When you bump the nerve, you are going to have temporary pain and tingling in the forearm distal to where the nerve goes over the lateral aspect of the elbow.

“Tennis elbow” is a sprain of the lateral aspect of the elbow referred to as lateral epicondylitis.

“Golfer’s elbow” is a sprain of the medial aspect of the elbow referred to as medial epicondylitis

“Student elbow” is caused by leaning on the elbow while studying. This compresses the bursa over the olecranon of the ulna, causing it to become inflamed and swollen. This is referred to as olecranon bursitis.

March/April 2012 ISSN-1059-6518 Volume 25 Number 2

By Frank Hubbell, DO

Lightning and Lightning Detectors

The Situation:

A summer camp was leading a day hike for a group of 7th and 8th graders in the mountains of North Carolina. The afternoon sky grew darker and darker and more threatening. Suddenly an afternoon thunderstorm came. The leaders saw a flash of lightning. They started to count the seconds until they heard a clap of thunder. Ten seconds elapsed between the flash and clap. Using the commonly accepted calculation methods, they determined that the bolt of lightning was only two miles away, definitely too close for safety. As they were getting the kids organized into a lightning drill, another bolt of lightning lit up the sky, and there was an immediate report of thunder. Quickly looking around, they realized that the lightning had struck in the immediate vicinity, and one of their students was down. He had been struck by lightning, electrocuted.

Thunderstorms are one of nature’s most spectacular events. At any given moment there are at least 2000 thunderstorms going on around the world. They not only provide us with a beautiful display of thunder and lightning, but their bolts of electricity also produce ozone (O3) which is extremely important because it absorbs UVC light in the upper atmosphere. This process is a very good thing because if UVC light were to reach the surface of the earth, all living things would be destroyed.

The Problem:

Lightning produced by thunderstorms also produces the life-threatening risk of being struck by lightning and electrocuted or incurring other injuries. Potential lightning strikes are one of the concerns that all outdoor centers, outdoor programs, and outdoor leaders have during the summer months when thunderstorms can be common. It is essential that these groups or individuals have plans for dealing with thunderstorms, especially when they are caught outside with nowhere to find shelter.

All outdoor leader education should include how, when, where, and what are the concerns about thunderstorms. They must have a well-practiced lightning drill plan for dealing with these situations.

March/April 2012 ISSN-1059-6518 Volume 25 Number 2

The INVASIVE Indo-Pacific Lionfish

By Frank Hubbell, DO

Illustration by T.B.R. Walsh

While recently in the Caribbean, we became acutely aware of a major problem for the spectacular underwater world of the Caribbean Sea – the invasive Lionfish.

The problem is that Lionfish do not belong in the Atlantic Ocean or the Caribbean Sea. They are an Indo-Pacific predatory fish, and that is exactly where they belong – in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

In the 1990’s, they were unintentionally introduced into the Atlantic, probably in the bilge water of ships returning to the Atlantic side of the world from the Indo-Pacific side. Today they have spread, as an invasive species, along the East Coast of the USA. In addition, they can be found in the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System and the wider Caribbean Sea.

A highly invasive species, they do not have any natural predators in these waters. In fact, in these marine environs, their only predator is we humans.

LIONFISH

Pterois volitans and Pterois miles are the two species, out of nine, of Lionfish that have invaded the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea. They have multiple spines in their fins containing toxic barbs.

The toxin in these barbs is a complex protein mixture of neuromuscular toxins and a neurotransmitter, acetylcholine. It is the acetylcholine that causes the untoward effects on the heart.

Hazard to Humans

Because they are not an aggressive fish, they will not attack you. However, they still present a hazard to humans who handle a caught fish or step on a fish and are impaled by the toxic spines in the fins.

Injuries are not uncommon in the Indo-Pacific Oceans, with about 30,000 – 40,000 injuries beings reported annually. But, the envenomation is rarely lethal.

Interview with Jed Williamson

/in Environemtal Injuries, Mountain rescue, prevention/by WMN EditorsISSN-1059-6518

The last several issues of the Wilderness Medicine Newsletter have been devoted to musculoskeletal and joint issues and the common injuries and treatments associated with these two topics. By contrast we wanted to present something a little different that addresses, at least, some of the underlying causes of accidents in the backcountry. To that end we spoke with Jed Williamson. Jed is well known in the climbing community for his participation in signature expeditions and as a former President of the American Alpine Club. He may be more generally recognized as the managing editor of Accidents in North American Mountaineering, an annual publication that lists accidents and offers assessments of the root causes of those accidents.

We have always thought of Jed first and foremost as an educator. As can be seen below, his credentials speak volumes about his contributions to the world of education, contributions that are sometimes overlooked in the context of his broader resume. We feel that Accidents in North American Mountaineering represents a tremendous resource of case studies, making it a valuable teaching tool. Through the following interview, we hope to make sure that everyone in the world of Emergency Medicine is aware of this resource. We are delighted to have the opportunity to talk with Jed and give him an opportunity to share some of his insights.

sometimes overlooked in the context of his broader resume. We feel that Accidents in North American Mountaineering represents a tremendous resource of case studies, making it a valuable teaching tool. Through the following interview, we hope to make sure that everyone in the world of Emergency Medicine is aware of this resource. We are delighted to have the opportunity to talk with Jed and give him an opportunity to share some of his insights.

The Editorial Staff

Wilderness Medicine Newsletter interview with Jed Williamson:

Snapshot Resume of John E. (Jed) Williamson

• Managing Editor of Accidents in North American Mountaineering (Annual Publication of the American Alpine Club) since 1974

• Former President of Sterling College, Craftsbury Common, VT, and faculty member in the Education Department at the University of New Hampshire.

• Former President of the American Alpine Club and current Chair of its Safety Advisory Council.

• First ascents in Canada, Alaska, and Mexico; expeditions to the Pamir, Minya Konka in western China, Bhutan, and Mount Everest.

• Former Board member: Association for Experiential Education, National Outdoor Leadership School, and Student Conservation Association.

• Current Boards: Upper Valley Educator’s Institute, Heartbeet Lifesharing, and Central Asia Institute.

• AMGA Certified Alpine Guide (Retired).

WMN: Jed, you are known for having a list of the top reasons that mountaineering accidents happen. Would you please review for the WMN what that list is?

JW: There are a lot of them, but when it comes to making decisions with a poor outcome, at the top of the list are: a desire to please other people and trying to stick to a schedule.

I mean clearly it varies from incident to incident. In addition, you have to look at other factors: for example, the big three—unsafe conditions, unsafe acts, and errors in judgment, but the top two are making decisions just to try to please other people or insisting on sticking with a schedule, particularly if conditions clearly dictate that it would be unwise to continue on.

Read more

Vaccines – Typhoid and Paratyphoid Fever

/in Immunizations, Typhoid/by WMN EditorsMay/June 2012 ISSN-1059-6518 Volume 25 Number 3

By Frank Hubbell, DO

What is Typhoid and Paratyphoid?

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid is a life-threatening illness caused by the bacterium Salmonella typhi. It is also known as gastric fever, abdominal typhus, infantile remittant fever, slow fever, nervous fever, and pythogenic fever.

Paratyphoid fever, also known as enteric fever, is a less serious illness that is also caused by Salmonella bacteria, but the symptoms are very similar to those of Typhoid Fever.

Warning: Typhoid fever is different from Typhus. Typhus is an illness caused by the bacterium Rickettsia while Typhoid is caused by Salmonella bacteria.

Pathophysiology of Typhoid:

Salmonella typhi lives only in humans – there is no other reservoir in nature besides humans.

The Salmonella typhi is spread from one person to another via the oral-fecal route where food or water has become contaminated by poor sanitation. Inadequate conditions have allowed the water source to become contaminated with human excrement – urine and feces, or by improper food handling and preparation.

Salmonella can also be spread by flying insects, such as flies, that feed on feces and then land and walk on food that you might then eat.

Flies: Their dirty little foot prints on your food is enough to spread Salmonella and other intestinal illnesses from one animal to another.

Once the Salomella bacterium has been consumed in food or water, it passes through the stomach into the intestinal tract where is multiplies and invades the mucosa wall. Within the mucosa wall the Salmonella bacteria are phagocystized (surrounded and consumed) by macrophages (white blood cells). If the bacteria manage to avoid the immune system in the gut wall, they will then invade and multiple in the blood stream.

It is the invasion and multiplication of the Salmonella in the bloodstream that causes the signs and symptoms of Typhoid.

Read more

Wilderness Treatment of Severe Infection: a First Hand Account

/in Fever, hands, Infection, Medical Response, Soft Tissue, Teaching Wilderness Medicine, Travel Medicine/by WMN EditorsMay/June 2012 ISSN-1059-6518 Volume 25 Number 3

While I was recently back in Zambia at Overland Missions teaching another Missionary Wilderness First Responder course as part of the Advanced Missions Training course that they do twice a year. I caught up with Mariel and after many hugs she told me this story and showed me the bone fragments from his finger, which she had saved for me to examine. I asked her to please write down this marvelous event, so we could share it with our readers.

Mariel is a staff member and one of the expedition leaders for Overland Missions based at Rapid 14 on the Zambezi River in the village of Nsongwe, Zambia. She is a great example of why we do what we do at SOLO. She recognized a life-threatening infection and applied the skills that she had been taught in her Missionary Wilderness First Responder course that she had taken at the Overland Missions base in Nsongwe the previous year. She saved his life and I am sure she will see him again on her return trip.

Frank Hubbell, DO Medical Editor Wilderness Medicine NewsletterThe Path to Peter

by Mariel Brantley

Winter in Africa will always take you by surprise. Your mind has to slightly bend to equate cold and Africa in the same realm. However, no matter how long it takes you to catch up with the paradoxical weather, it doesn’t change the fact that come morning, you will struggle to get your blood flowing again because of the cold. It was day two of our expedition. We hit the dirt path at 9am and had no plan of returning until we found what we were looking for. Equipped with a team of five and one translator, we were searching for the unreached. We pushed ourselves to go faster, further, and harder than the day before. I knew we were finally meeting our goal when we found ourselves on the far side of the hills, delicately dangled in the balance of a broken log and four slippery stones while crossing one of the river beds.

If I had any doubt in my mind if I was awake, it definitely went away as we walked into the first village. As I stood there looking at the villagers, it was as though my sense of smell overpowered my sight. I immediately knew something was wrong. After all, the scent of decaying flesh is unmistakable. Before I could get the words out, I was already making my way toward a man standing in the back. I said, “Who is hurt here? Someone is sick. You sir, what is wrong?” The man looked up at me with the look of shame and fear. I approached him and saw a dirty, tattered strip of cloth covering his finger and asked him to remove it. He slowly removed the cloth to reveal an extremely swollen and infected finger. I asked his name and what had happened. The man said his name was Peter, then explained he had been in a fight and was bitten by the man who attacked him. He said that it had happened about two months prior. My eyes darted across every detail I could absorb like one of those rapid freeze frame shots you see in a movie. I observed the wound and could clearly identify the track mark of the infection trailing all the way up his arm, past his elbow and to the middle of his bicep. Severe infection + closed wound + clear track line + raised body temperature = serious trouble. I looked up at him with a sense of urgency and said, “Sir, please, you must come with us to our camp.”

infection trailing all the way up his arm, past his elbow and to the middle of his bicep. Severe infection + closed wound + clear track line + raised body temperature = serious trouble. I looked up at him with a sense of urgency and said, “Sir, please, you must come with us to our camp.”

Read more

Elbow Injuries and Ankle Injuries

/in Ankle, Elbow, Feet, Musculoskeletal/by WMN EditorsISSN-1059-6518

Elbow Injuries and Ankle Injuries

By Frank Hubbell, DO

Illustrations By T.B.R. Walsh

THE SITUATION:

A couple is hiking down a trail into the Grand Canyon, enjoying the day and looking forward to reaching some shade at the bottom. The trail is in good shape with the occasional rock in the middle of the trail. The female companion unfortunately stubs her toe on a rock and falls. She falls forward, downhill, with a 40# pack on her back. She instinctively reaches out with her right hand to control the fall. As her right hand impacts the ground with her arm straight, she feels an intense searing pain in her right elbow, a sharp snap, and her arm collapses. Crumbling onto the trail, she immediately rolls over and grasps her right elbow in her left hand, letting her companion know that her right elbow is in excruciating pain.

Upon examination, he finds that the elbow is very tender to palpation and is locked in position at 90 degrees of flexion. The elbow is deformed and looks like the butt of a gun, a gunstock. He also notes a decreased sensation in her fingers and no radial pulse at her wrist. Over the next half hour her right hand goes from pale to cyanotic, with pins and needles sensation in her fingers, and she is unable to move her fingers.

ELBOW FACTS:

Elbow pain is the second most common reason to see an orthopedic surgeon, the first reason being shoulder pain.

The “funny bone” is not a bone. It is actually the ulnar nerve. When you bump the nerve, you are going to have temporary pain and tingling in the forearm distal to where the nerve goes over the lateral aspect of the elbow.

“Tennis elbow” is a sprain of the lateral aspect of the elbow referred to as lateral epicondylitis.

“Golfer’s elbow” is a sprain of the medial aspect of the elbow referred to as medial epicondylitis

“Student elbow” is caused by leaning on the elbow while studying. This compresses the bursa over the olecranon of the ulna, causing it to become inflamed and swollen. This is referred to as olecranon bursitis.

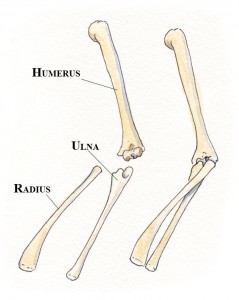

THE ANATOMY OF THE ELBOW:

Bones:

There are 3 bones that make up the elbow joint.

Humerus – the upper arm

Radius – the forearm

Ulna – the forearm

Read more

Lightning and Lightning Detectors

/in Burns, Environemtal Injuries, Heat related Injuries, Lightning, Survival, Weather/by WMN EditorsMarch/April 2012 ISSN-1059-6518 Volume 25 Number 2

By Frank Hubbell, DO

Lightning and Lightning Detectors

The Situation:

A summer camp was leading a day hike for a group of 7th and 8th graders in the mountains of North Carolina. The afternoon sky grew darker and darker and more threatening. Suddenly an afternoon thunderstorm came. The leaders saw a flash of lightning. They started to count the seconds until they heard a clap of thunder. Ten seconds elapsed between the flash and clap. Using the commonly accepted calculation methods, they determined that the bolt of lightning was only two miles away, definitely too close for safety. As they were getting the kids organized into a lightning drill, another bolt of lightning lit up the sky, and there was an immediate report of thunder. Quickly looking around, they realized that the lightning had struck in the immediate vicinity, and one of their students was down. He had been struck by lightning, electrocuted.

Thunderstorms are one of nature’s most spectacular events. At any given moment there are at least 2000 thunderstorms going on around the world. They not only provide us with a beautiful display of thunder and lightning, but their bolts of electricity also produce ozone (O3) which is extremely important because it absorbs UVC light in the upper atmosphere. This process is a very good thing because if UVC light were to reach the surface of the earth, all living things would be destroyed.

The Problem:

Lightning produced by thunderstorms also produces the life-threatening risk of being struck by lightning and electrocuted or incurring other injuries. Potential lightning strikes are one of the concerns that all outdoor centers, outdoor programs, and outdoor leaders have during the summer months when thunderstorms can be common. It is essential that these groups or individuals have plans for dealing with thunderstorms, especially when they are caught outside with nowhere to find shelter.

All outdoor leader education should include how, when, where, and what are the concerns about thunderstorms. They must have a well-practiced lightning drill plan for dealing with these situations.

Read more

Indo-Pacific Lionfish

/in Bites and Stings, Environemtal Injuries, Fever, Infection, Shortness of breath, Travel Medicine/by WMN EditorsMarch/April 2012 ISSN-1059-6518 Volume 25 Number 2

The INVASIVE Indo-Pacific Lionfish

By Frank Hubbell, DO

Illustration by T.B.R. Walsh

While recently in the Caribbean, we became acutely aware of a major problem for the spectacular underwater world of the Caribbean Sea – the invasive Lionfish.

The problem is that Lionfish do not belong in the Atlantic Ocean or the Caribbean Sea. They are an Indo-Pacific predatory fish, and that is exactly where they belong – in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

In the 1990’s, they were unintentionally introduced into the Atlantic, probably in the bilge water of ships returning to the Atlantic side of the world from the Indo-Pacific side. Today they have spread, as an invasive species, along the East Coast of the USA. In addition, they can be found in the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System and the wider Caribbean Sea.

A highly invasive species, they do not have any natural predators in these waters. In fact, in these marine environs, their only predator is we humans.

LIONFISH

Pterois volitans and Pterois miles are the two species, out of nine, of Lionfish that have invaded the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea. They have multiple spines in their fins containing toxic barbs.

The toxin in these barbs is a complex protein mixture of neuromuscular toxins and a neurotransmitter, acetylcholine. It is the acetylcholine that causes the untoward effects on the heart.

Hazard to Humans

Because they are not an aggressive fish, they will not attack you. However, they still present a hazard to humans who handle a caught fish or step on a fish and are impaled by the toxic spines in the fins.

Injuries are not uncommon in the Indo-Pacific Oceans, with about 30,000 – 40,000 injuries beings reported annually. But, the envenomation is rarely lethal.

Read more