OK here we go, everything that you ever wanted to know about allergies, but were afraid to ask.

What is an allergy?

An allergy, or allergic reaction, is a hypersensitivity reaction, or over-reaction, of our immune system in response to an antigen.

What is our immune system?

Simply put, the immune system is a series of biomolecules, chemical reactions. and cells that protect us from invading foreign organisms through a variety of mechanisms. The purpose of our immune system is to recognize self from non-self, and if it is non-self, the immune system will destroy the invader and make a memory of the invader to recognize it in the future. This memory is maintained and mediated by antibodies produced by B cells also called plasma cells.

What is an antigen (Ag)?

An antigen is a toxin or other foreign substance that induces an immune response and the production of antibodies. Antigens are usually proteins or are attached to proteins.

Are the official procedure or system of rules governing an agency. In this case EMS.

These rules are produced by and established by an authoritative body, such as a state EMS Bureau, not a school, college, university, business, or individual.

This continues to be a gray area in the world of EMS that needs to be discussed. The practice of providing care outside of the “Golden Hour” and using techniques that are not within the usual scope of practice of EMS remains controversial and, most importantly, has never been tested in a court of law, which would establish precedence.

This becomes more important as EMS continues to mature and become better defined and embedded in rules and law. The idea of having to apply different standards of care based on time to definitive care is accepted, but those techniques used in the austere environment remain somewhat illusive with wide variations.

The term, evidence-based medicine, is commonly used to help define and justify medical care on all levels, but it does not exist for the wilderness environment. There are just simply not enough backcountry rescues or case studies in the different areas of providing care to test and prove the validity of the techniques. So, experts come together to provide a “best practices” based on their collective experiences.

https://www.wildernessmedicinenewsletter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/wmnlogo20151.png00WMN Editorshttps://www.wildernessmedicinenewsletter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/wmnlogo20151.pngWMN Editors2019-11-18 14:25:272019-11-18 14:25:27Practicing Wilderness Medicine and Protocols

Here at SOLO we are hearing this question more and more from our instructors. Frank Hubbell, D.O., Josh MacMillan, Paramedic, and Paul MacMillan, CAGS, WEMT, we believe this is important information to have for two reasons. First, because you are more in tune with what their medical needs may be and second, you can treat the patient with the dignity they deserve. This information is so important as the patient will travel through the emergency medical system. With this being said, there are two great articles out there from the New York Times to read. One is titled Gay and Transgender Patients to Doctors: We’ll Tell. Just Ask., by Jan Hoffman dated May 29, 2017. The second article is titled A Transgender Learning Gap in the Emergency Room, by Helen Ouyang, M.D. dated April 13, 2017. Both of these articles highlight the learning curve we are all on and the need for more formal research that needs to be done to provide the best possible care to people.

The first steps you should take is knowing the Sexual Identity and Gender Identity Definitions:

https://www.wildernessmedicinenewsletter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/wmnlogo20151.png00WMN Editorshttps://www.wildernessmedicinenewsletter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/wmnlogo20151.pngWMN Editors2019-02-19 21:16:002019-02-22 15:45:23Do EMS Providers Need to Know a Patient’s Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity?

SOLO recently updated its tourniquet curriculum to incorporate the latest evidence. A growing trove of research in recent decades has confirmed that tourniquets are extremely effective at stopping massive bleeds. When used appropriately, they have minimal complications. Tourniquets have been a contentious piece of the pre-hospital medical kit for thousands of years. The emergency medical community has swung back and forth on their merits and drawbacks during that time. The era of evidence-based medicine itself is relatively new. It’s only since the war in Vietnam that researchers have begun to study tourniquets systematically. This research has led to improved education and much greater success.

A tourniquet is still a last resort to stop severe extremity bleeding in the wilderness setting. Only use one if there is a traumatic amputation, obvious arterial bleeding, or if direct pressure will not stop the bleeding. They should never be used on minor bleeds. Using a tourniquet on minor bleeds or shoddy improvisation by inadequately trained caregivers are some of the reasons that many surgeons vilified tourniquets for so long.

The major change in the curriculum is that tourniquets are no longer just for life-over-limb situations. They are a life-saving technique that should be used without hesitation. So long as the tourniquet can be removed within a couple of hours, patients are unlikely to lose the limb. One recent study looked at 232 patients who had tourniquets applied to 309 limbs. Not a single limb was lost to amputation because of the use of tourniquets.

Evidenced-based medical research has shown that the proper position for the tourniquet is two to three inches above the site of bleeding. It is important to take a few seconds and locate the site of bleeding and then place the tourniquet. You cannot place a tourniquet over a joint, the knee or the elbow. If necessary, move just proximal to the joint and place the tourniquet.

https://www.wildernessmedicinenewsletter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/wmnlogo20151.png00WMN Editorshttps://www.wildernessmedicinenewsletter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/wmnlogo20151.pngWMN Editors2018-03-09 19:40:312018-03-09 20:29:00Proper Use of Tourniquets – 2018

“Those who travel in desert places do indeed meet with creatures surpassing all description.”

–Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

Deserts are generally inhospitable places. They’re either too hot, too cold, too dry, or too windy. Sandstorms, monsoons, and flash floods ravage the land. The plants are spiky and the animals are venomous. Nonetheless, people like to visit the desert. A lot of people. Because despite the downsides, deserts are beautiful.

There are three distinct hot deserts in the American Southwest – the Chihuahuan, the Sonoran, and the Mojave. The Chihuahuan Desert covers southern New Mexico, western Texas, the extreme southeastern corner of Arizona, and extends into the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Durango. The Sonoran Desert extends from southern Arizona and southeastern California into the Mexican state of Sonora. The Mojave covers southeastern California, southern Nevada, northwestern Arizona, and a tiny corner of southwestern Utah. The boundaries of the three deserts are determined by the distribution of plant and animal species. In some cases, the individual deserts are bounded by mountain ranges that form “sky islands” of more temperate habitat. Hot deserts differ from cold deserts (like the Great Basin farther north) in that most of their precipitation comes in the form of rain, as opposed to snow.

Deserts are home to a startlingly wide variety of plants and animals that have adapted to the harsh conditions. The Chihuahuan Desert is one of the most biodiverse arid regions on Earth. Most desert animals are not actually venomous. Regardless, all wild animals should be appreciated only from a safe distance. The creatures that are venomous include reptiles, such as snakes and Gila monsters, and arachnids, including spiders, scorpions, and to a lesser degree, tarantulas. This article describes many of the venomous species that are native to the region.

REPTILES

Rattlesnakes

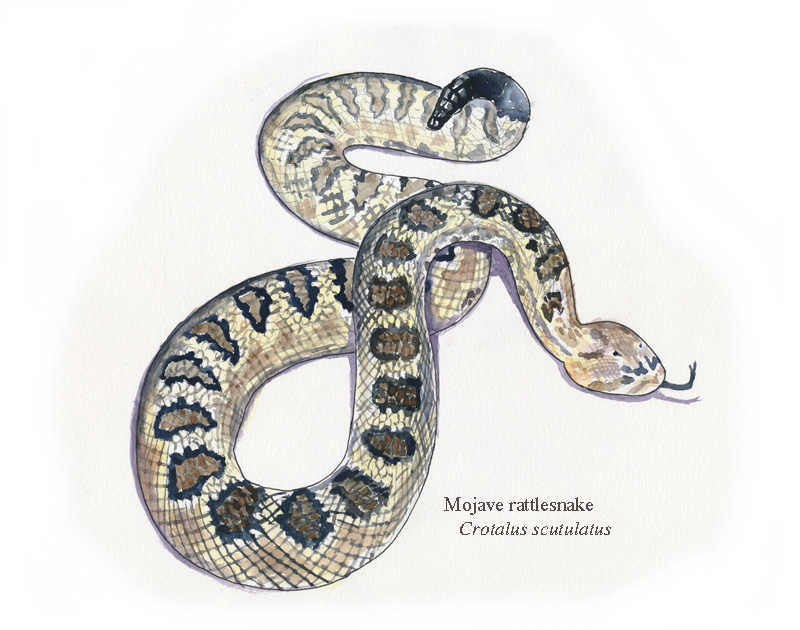

Rattlesnakes live nearly everywhere in the United States, but they are especially abundant in the southwest. There are 36 species in the western hemisphere, 17 in the U.S., and 14 in the southwestern deserts. The most poisonous of these are the Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus), with an LD50 SC of 0.31 mg/kg, and the tiger rattlesnake (Crotalus tigris), with an LD50 SC of 0.21 mg/kg. The LD50, also known as the median lethal dose, indicates how much venom it takes for a snake to kill 50% of its prey. The lower the number, the more potent the venom. The “SC” refers to subcutaneous injection, which is the most common way that humans are exposed to the venom. For comparison, the timber rattlesnake of the Eastern United States has an LD50 SC of 2.25 mg/kg.

https://www.wildernessmedicinenewsletter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/wmnlogo20151.png00WMN Editorshttps://www.wildernessmedicinenewsletter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/wmnlogo20151.pngWMN Editors2017-09-07 19:59:012017-09-07 20:05:14Venomous Critters of the Southwestern Deserts

FACT: 1.1 billion people cross international borders every year!

How many of these international travelers know what is waiting for them at the end of the runway or on the other side of the border? At home you are most likely safe. You have potable drinking water, safe food to eat, reliable power, screens on your windows and doors to protect you from marauding insects, and have excellent, available, immediate health care when needed. To put it simply, most of us live in a bubble. The question is, are you sure that you are prepared for the times when you leave the safety of your bubble?

This is the material that we use in our Travel Clinic to help educate and prepare people for international travel. We offer it here for your review and, if necessary, take with you to a consult for travel medicine.

TRAVEL PLANS:

Make Out a Trip Itinerary:

When are you going and for how long?

Leaving:

Returning:

Where are you going?

Rural:

Urban:

What are you planning on doing while there?

Travel plans?

How are you planning on getting around?

Previous International Travel History:

When did you go?

Where did you go and for how long?

MEDICAL HISTORY:

Past Medical and Surgical History:

Allergies

Medications – name and dosage

Immune Status – any history of autoimmune diseases, HIV, DM

https://www.wildernessmedicinenewsletter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/wmnlogo20151.png00WMN Editorshttps://www.wildernessmedicinenewsletter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/wmnlogo20151.pngWMN Editors2017-05-03 12:54:212017-05-03 12:54:21YOUR PASSPORT TO INTERNATIONAL TRAVEL HEALTH and SAFETY

AN ALLERGY PRIMER

/in Allergies, Asthma/by WMN EditorsISSN-1059-6518

Volume 34 Number 1

By Frank Hubbell, DO

OK here we go, everything that you ever wanted to know about allergies, but were afraid to ask.

What is an allergy?

An allergy, or allergic reaction, is a hypersensitivity reaction, or over-reaction, of our immune system in response to an antigen.

What is our immune system?

Simply put, the immune system is a series of biomolecules, chemical reactions. and cells that protect us from invading foreign organisms through a variety of mechanisms. The purpose of our immune system is to recognize self from non-self, and if it is non-self, the immune system will destroy the invader and make a memory of the invader to recognize it in the future. This memory is maintained and mediated by antibodies produced by B cells also called plasma cells.

What is an antigen (Ag)?

An antigen is a toxin or other foreign substance that induces an immune response and the production of antibodies. Antigens are usually proteins or are attached to proteins.

What is an antibody (Ab)?

Read more

Practicing Wilderness Medicine and Protocols

/in Medical Response, Mountain rescue, Treatment/by WMN EditorsISSN-1059-6518

Volume 33 Number 1

Protocols:

Frank Hubbell, D.O.

Are the official procedure or system of rules governing an agency. In this case EMS.

These rules are produced by and established by an authoritative body, such as a state EMS Bureau, not a school, college, university, business, or individual.

This continues to be a gray area in the world of EMS that needs to be discussed. The practice of providing care outside of the “Golden Hour” and using techniques that are not within the usual scope of practice of EMS remains controversial and, most importantly, has never been tested in a court of law, which would establish precedence.

This becomes more important as EMS continues to mature and become better defined and embedded in rules and law. The idea of having to apply different standards of care based on time to definitive care is accepted, but those techniques used in the austere environment remain somewhat illusive with wide variations.

The term, evidence-based medicine, is commonly used to help define and justify medical care on all levels, but it does not exist for the wilderness environment. There are just simply not enough backcountry rescues or case studies in the different areas of providing care to test and prove the validity of the techniques. So, experts come together to provide a “best practices” based on their collective experiences.

Read more

Do EMS Providers Need to Know a Patient’s Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity?

/in Patient Assessment, Rescue Training, Treatment/by WMN EditorsISSN-1059-6518

Volume 32 Number 1

By Paul MacMillan, EMT

Here at SOLO we are hearing this question more and more from our instructors. Frank Hubbell, D.O., Josh MacMillan, Paramedic, and Paul MacMillan, CAGS, WEMT, we believe this is important information to have for two reasons. First, because you are more in tune with what their medical needs may be and second, you can treat the patient with the dignity they deserve. This information is so important as the patient will travel through the emergency medical system. With this being said, there are two great articles out there from the New York Times to read. One is titled Gay and Transgender Patients to Doctors: We’ll Tell. Just Ask., by Jan Hoffman dated May 29, 2017. The second article is titled A Transgender Learning Gap in the Emergency Room, by Helen Ouyang, M.D. dated April 13, 2017. Both of these articles highlight the learning curve we are all on and the need for more formal research that needs to be done to provide the best possible care to people.

The first steps you should take is knowing the Sexual Identity and Gender Identity Definitions:

Read more

Proper Use of Tourniquets – 2018

/in Bandaging, Control bleeding, Medical Response, Trauma, Treatment/by WMN EditorsISSN-1059-6518

Proper Use of Tourniquets – 2018

By Jeff DeBellis

Illustrations by T.B.R. Walsh

SOLO recently updated its tourniquet curriculum to incorporate the latest evidence. A growing trove of research in recent decades has confirmed that tourniquets are extremely effective at stopping massive bleeds. When used appropriately, they have minimal complications. Tourniquets have been a contentious piece of the pre-hospital medical kit for thousands of years. The emergency medical community has swung back and forth on their merits and drawbacks during that time. The era of evidence-based medicine itself is relatively new. It’s only since the war in Vietnam that researchers have begun to study tourniquets systematically. This research has led to improved education and much greater success.

A tourniquet is still a last resort to stop severe extremity bleeding in the wilderness setting. Only use one if there is a traumatic amputation, obvious arterial bleeding, or if direct pressure will not stop the bleeding. They should never be used on minor bleeds. Using a tourniquet on minor bleeds or shoddy improvisation by inadequately trained caregivers are some of the reasons that many surgeons vilified tourniquets for so long.

The major change in the curriculum is that tourniquets are no longer just for life-over-limb situations. They are a life-saving technique that should be used without hesitation. So long as the tourniquet can be removed within a couple of hours, patients are unlikely to lose the limb. One recent study looked at 232 patients who had tourniquets applied to 309 limbs. Not a single limb was lost to amputation because of the use of tourniquets.

How to Apply a Tourniquet:

There are a number of commercial tourniquet models available. The two that the US Army Institute of Surgical Research identifies as being 100% effective are the Combat Application Tourniquet (CAT) and the SOF Tactical Tourniquet (SOFTT). A properly improvised and placed tourniquet can work just as well as a commercial model.

Evidenced-based medical research has shown that the proper position for the tourniquet is two to three inches above the site of bleeding. It is important to take a few seconds and locate the site of bleeding and then place the tourniquet. You cannot place a tourniquet over a joint, the knee or the elbow. If necessary, move just proximal to the joint and place the tourniquet.

Read more

Venomous Critters of the Southwestern Deserts

/in Bites and Stings, Neurological, Poisons/by WMN EditorsISSN-1059-6518

Venomous Critters of the Southwestern Deserts

By Jeff DeBellis

Illustrations by T.B.R. Walsh

“Those who travel in desert places do indeed meet with creatures surpassing all description.”

–Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

Deserts are generally inhospitable places. They’re either too hot, too cold, too dry, or too windy. Sandstorms, monsoons, and flash floods ravage the land. The plants are spiky and the animals are venomous. Nonetheless, people like to visit the desert. A lot of people. Because despite the downsides, deserts are beautiful.

There are three distinct hot deserts in the American Southwest – the Chihuahuan, the Sonoran, and the Mojave. The Chihuahuan Desert covers southern New Mexico, western Texas, the extreme southeastern corner of Arizona, and extends into the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Durango. The Sonoran Desert extends from southern Arizona and southeastern California into the Mexican state of Sonora. The Mojave covers southeastern California, southern Nevada, northwestern Arizona, and a tiny corner of southwestern Utah. The boundaries of the three deserts are determined by the distribution of plant and animal species. In some cases, the individual deserts are bounded by mountain ranges that form “sky islands” of more temperate habitat. Hot deserts differ from cold deserts (like the Great Basin farther north) in that most of their precipitation comes in the form of rain, as opposed to snow.

Deserts are home to a startlingly wide variety of plants and animals that have adapted to the harsh conditions. The Chihuahuan Desert is one of the most biodiverse arid regions on Earth. Most desert animals are not actually venomous. Regardless, all wild animals should be appreciated only from a safe distance. The creatures that are venomous include reptiles, such as snakes and Gila monsters, and arachnids, including spiders, scorpions, and to a lesser degree, tarantulas. This article describes many of the venomous species that are native to the region.

REPTILES

Rattlesnakes

Rattlesnakes live nearly everywhere in the United States, but they are especially abundant in the southwest. There are 36 species in the western hemisphere, 17 in the U.S., and 14 in the southwestern deserts. The most poisonous of these are the Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus), with an LD50 SC of 0.31 mg/kg, and the tiger rattlesnake (Crotalus tigris), with an LD50 SC of 0.21 mg/kg. The LD50, also known as the median lethal dose, indicates how much venom it takes for a snake to kill 50% of its prey. The lower the number, the more potent the venom. The “SC” refers to subcutaneous injection, which is the most common way that humans are exposed to the venom. For comparison, the timber rattlesnake of the Eastern United States has an LD50 SC of 2.25 mg/kg.

Read more

YOUR PASSPORT TO INTERNATIONAL TRAVEL HEALTH and SAFETY

/in Asprin, Disease, Immunizations, Travel Medicine/by WMN EditorsVolume 30 Number 1 ISSN:1059-6518

By Frank Hubbell, DO

FACT: 1.1 billion people cross international borders every year!

How many of these international travelers know what is waiting for them at the end of the runway or on the other side of the border? At home you are most likely safe. You have potable drinking water, safe food to eat, reliable power, screens on your windows and doors to protect you from marauding insects, and have excellent, available, immediate health care when needed. To put it simply, most of us live in a bubble. The question is, are you sure that you are prepared for the times when you leave the safety of your bubble?

This is the material that we use in our Travel Clinic to help educate and prepare people for international travel. We offer it here for your review and, if necessary, take with you to a consult for travel medicine.

TRAVEL PLANS:

Make Out a Trip Itinerary:

When are you going and for how long?

Leaving:

Returning:

Where are you going?

Rural:

Urban:

What are you planning on doing while there?

Travel plans?

How are you planning on getting around?

Previous International Travel History:

When did you go?

Where did you go and for how long?

MEDICAL HISTORY:

Past Medical and Surgical History:

Allergies

Medications – name and dosage

Immune Status – any history of autoimmune diseases, HIV, DM

Read more